Peter Fox was my mother’s fiancé, murdered in Cyprus in 1956. His remains have rested in an unmarked grave for nearly seventy years: his bones buried deep under the hard, hot soil of the British Cemetery of Nicosia.

These past seventy years, Peter has been nothing more than a missing name, a missing stone, a forgotten life-history. And, more poignantly, a severed love story, brutally cut off by the bullet of a Greek Cypriot terrorist.

A terrorist? That’s what the killer was called back then – so by definition, yes. But also a man with his own values and convictions: someone who believed – together with thousands of other Cypriots at the time – that his island should be an independent Cyprus, not a British Colony. I imagine the terrorist himself will be dead by now. I wonder where his bones lie? Did he have the honour of lying beneath a marked grave, unlike the young Englishman he shot dead?

Peter Fox. A tall, handsome man who I never knew – but, through my mother’s countless stories that filled and dazzled my entire upbringing – someone who I loved like a surrogate father. A noble, passionate man, but also with a wicked sense of humour. A flirt, too – much to my mother’s chagrin on many an occasion. Members of the opposite sex couldn’t keep their eyes off him. A journalist by profession, but also a deep thinker, philosopher and political analyst. Someone who believed in the equality of all men; who memorised the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and believed that every child should be taught the words in school.

Someone who was visiting a fellow journalist-friend working in Kyrenia at the time, and hoping, during his visit, to report on the Suez crisis. It was November 1956, and the whole world was talking about Suez. What better a place for a young, ambitious reporter to be temporarily stationed than the beautiful, perfectly located island of Cyprus?

So, when a vacancy appeared in the local colonial newspaper, The Times of Cyprus, Peter must have thought the gods were at last looking down on him with kindness. He applied for the job – which had been made vacant due to the murder of the previous journalist, Angus MacDonald – and, joy upon joy, he was immediately offered the position by the paper’s founder and chief editor, Charles Foley.

Peter wrote home to his fiancee with these joyous but prophetic words, which still bring a lump to my throat every time I re-read them. (I have an entire boxful of Peter’s letters to my mother.) Here’s the opening paragraph of his last letter:

My darling Chubs,

I am now working (frightening work) for The Times of Cyprus, replacing Angus McDonald, who EOKA murdered as a British spy. If they decide I am his successor, you may just be able to reach me with a letter – if you sit down right away – before I get it in the back.

Peter ‘got in the back’ on the afternoon of December 8th 1956 – shot dead while standing outside the Katsellis cinema in Kyrenia, contemplating which film to see that evening. He died in the ambulance on the way to hospital. In later years, my mother always told me how she deeply regretted not having been with him in those final moments, holding his hand as he drew his last, dying breath.

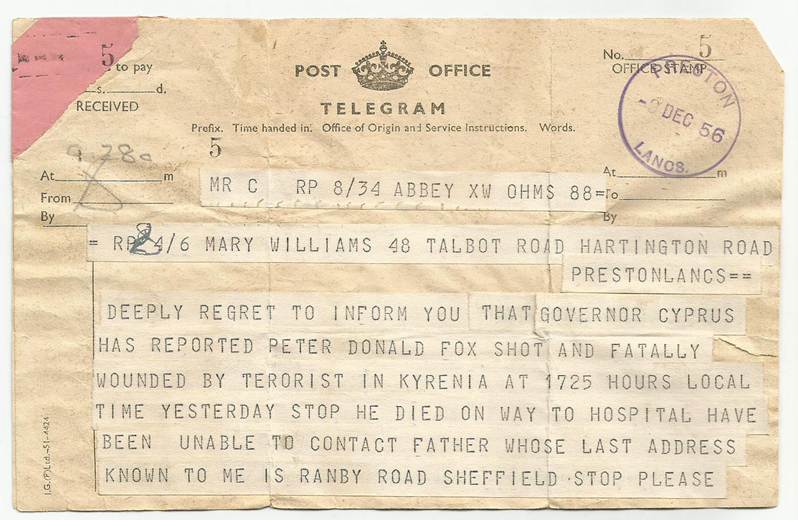

But she wasn’t with him. She was in Preston, deep in the industrial bowels of northern England, when she received the telegram from the Colonial Office in Nicosia, and read the words which would change her life forever:

The following week, she received Peter’s posthumous letter. I remember my aunt telling me, many years later, how receiving that final letter from Peter, after he was already dead, broke my mother’s heart all over again. Just when she thought that nothing in life could ever again hurt as much as the pain of that telegram, Fate proved her wrong.

So much pain. So much grief. So much regret. Why hadn’t they at least married before he died?

And then, one day, seventy years later, I decided to change all that. I decided to bring Peter’s memory back to life.

Via the pages of my current novel, I have succeeded in resurrecting his brief, forgotten history and his severed love for a woman who never stopped loving him – even when she married someone else on the rebound. (In fact, it was the journalist-friend who Peter had been staying with in Kyrenia – my future father!)

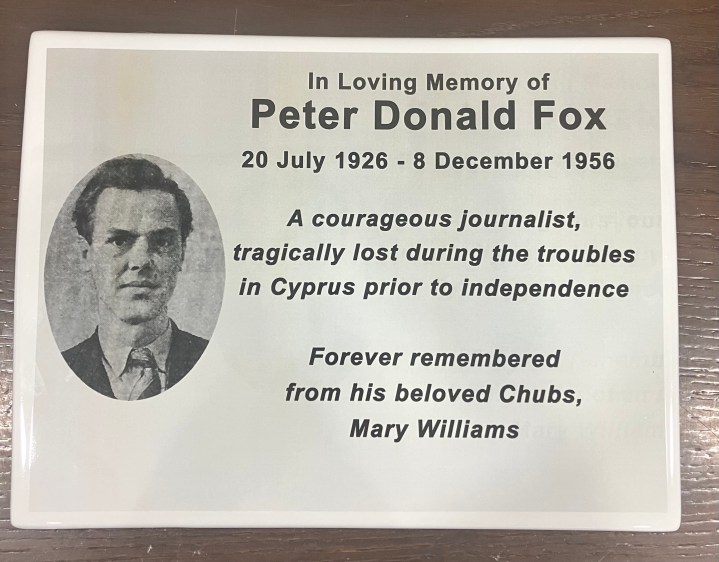

Moreover, by erecting a plaque on the wall of the British Cemetery of Nicosia just a few weeks ago – near the exact spot where Peter’s remains lie – I have managed to give him back his name and his short-lived presence in this world, now to be remembered with dignity and love.

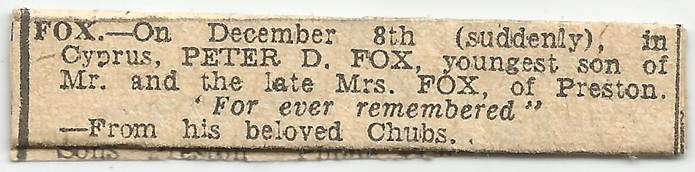

And finally, I think of my late mother, who posted this obituary in the Lancashire Evening Post, where Peter had started his short-lived journalist’s career.

ADDENDUM

Many thanks to George Kazantsis of Nicosia, who was instrumental in finding the exact spot where Peter’s remains lay in the British Cemetery of Nicosia. Thank you also to Helen Klostis and David Hardacre of St Paul’s Anglican Cathedral, Nicosia, who supported me throughout my quest and helped enormously in organising the erection of the plaque. Thank you also to Pavlos Melas for creating the plaque.

And finally, huge thanks to Therese Mikhailovsky – my mother’s young friend in Kyrenia when I was a toddler, and now my own beloved friend, still living in Cyprus.

Note: EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston) was a Greek Cypriot nationalist guerrilla organisation that fought to end British rule in Cyprus and to achieve union with Greece (Enosis), primarily active between 1955 and 1959.

A beautiful Epitaph. Like all of your writing, beautiful and full of feeling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much 💓

LikeLike

Seems you have two fathers.

Btw, the inserts dont show in the text (pictures?).

LikeLike

Now they show as I enter your actual text (not in my email).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Phew, that’s a relief! 😊

LikeLike

This is a really touching story to read

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person